End of the Golden Era: Railroads Decline and Union Station’s New Life

In the mid-20th century, Ogden still proudly bore the nickname “Junction City” – a bustling rail hub at the Crossroads of the West. But by the 1960s, the golden era of passenger rail was waning. The rise of airlines and the new interstate highways siphoned travelers away from trains. Daily passenger trains serving Ogden plummeted from dozens a day after WWII to just two in each direction by the late 1960s. Union Station, once the grand depot pulsing with crowds, grew eerily quiet except for a few railroad employees. In 1969 the railroad tore out over half of the passenger platforms and even demolished the old commissary that had serviced cross-country trains.

Change accelerated in 1971, when Amtrak took over U.S. passenger rail service. Ogden was left with only one daily train each way – the Amtrak “Pioneer” – as private railroads lost interest in the depot. Fearing the beloved station might be abandoned or even demolished, Ogden’s leaders and citizens mobilized to save it. During the 1969 Golden Spike centennial, local visionaries first proposed turning Union Station into a museum and community center. Mayor Bart Wolthuis and the city formally asked Union Pacific to donate the now mostly-empty station for preservation. After years of negotiations – and even trial runs like art shows held in the vacant waiting hall – Union Pacific finally agreed. In 1977, ownership of the grand Spanish Colonial Revival station building transferred to Ogden City (with a long-term land lease) and renovations began to transform it into a museum complex.

The rebirth of Union Station as a heritage site culminated with a dedication ceremony in 1978. Union Pacific’s historic steam locomotive 8444 chugged into town for the occasion, greeted by cheering crowds. Over the following decade the station became home to the Utah State Railroad Museum (designated in 1988) and other museum attractions. Meanwhile, passenger rail service faded out completely – Amtrak dropped Ogden from its timetable in 1983, and the last Pioneer train pulled away in May 1997. For the first time in 128 years, no scheduled passenger trains stopped at Ogden’s Union Station. The iron horse era had ended, but the station endured as a civic treasure – “recycled” into a museum, event venue, and monument to Ogden’s railroading heritage.

This twilight of the railroad age in the 1960s–70s sent ripples through Ogden’s economy and culture. Hotels, shops, and restaurants near the depot that once thrived on rail traveler patronage now struggled or closed. The venerable 25th Street, just east of the station, fell into dereliction. Once notorious worldwide as “Two-Bit Street” – a red-light district of saloons, gambling dens and brothels catering to rail crews and soldiers – by the late 1950s and ’60s it had decayed into Ogden’s skid row. Many historic buildings were boarded up or torn down, and transient vagrants occupied rundown hotels. Civic leaders initially saw blight, but preservationists saw potential in the charming but faded brick structures. In the 1970s, spurred by America’s Bicentennial enthusiasm for heritage, locals formed a Historic 25th Street Committee and pushed to save the district. Mayor Stephen Dirks – who believed Ogden was “on the threshold of a renaissance in the revitalization of lower 25th Street” – championed a 25th Street Master Plan in 1977. By 1976, two blocks of 25th Street earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places, cementing its status as “Historic 25th Street”.

Under this plan, Ogden committed to restore 25th Street’s century-old buildings and revive downtown rather than bulldoze it. Over the ensuing years, the city assisted building owners with low-interest renovation loans and even bought key properties to prevent their demolition. The once-bawdy street slowly came back to life: original brick façades were repaired, vintage Victorian lampposts and planters added, and new businesses moved in – from antique shops to cafes and even a local craft brewery. By the end of the 20th century, 25th Street had transformed from a place “upstanding” citizens long avoided into “a trendy neighborhood” where an eclectic mix of tourists, office workers, and blue-collar regulars now mingled. The street’s “personality and character” survived intact, as city planner Richard McConkie noted – and it became a point of pride in Ogden’s downtown revival.

Suburban Boom, Malls and Main Street Preservation

While downtown Ogden grappled with change in the 1960s–70s, the wider region underwent a suburban boom. Construction of Interstate 15 straight through Davis County in the 1960s supercharged suburbia, suddenly cutting travel times between Ogden, Salt Lake City, and Hill Air Force Base. Farmland that once separated Weber and Davis County towns began sprouting tract homes and shopping centers. Layton, Clearfield, and other communities south of Ogden doubled and tripled in population as families embraced the suburban dream. Davis County’s population exploded from about 65,000 in 1960 to 147,000 by 1980. Hill Air Force Base, straddling the Davis/Weber line, remained a linchpin of growth – established during WWII, Hill AFB by the 1970s was (and remains) one of Utah’s largest employers, attracting thousands of civilian workers to the area. Meanwhile in Clearfield, the massive Navy Supply Depot from WWII was decommissioned in 1962 and reborn as the private Freeport Center, a sprawling industrial park that housed dozens of warehouses and manufacturers. By the 1980s the Freeport Center boasted over 7 million square feet of warehouse space and some 7,000 employees, securing its place as Utah’s largest distribution center. The synergy of federal defense jobs and new freeway access fueled prosperity in the suburbs – even as it diverted retail and development energy away from Ogden’s historic core.

In response, Ogden city leaders in the late 1970s pursued a bold plan to recapture shoppers and revitalize downtown: build a modern indoor shopping mall right in the heart of the city. Under Mayor Dirks’ administration, Ogden joined the nationwide mall-building trend. Aging sections of downtown were cleared, and by 1980 the new Ogden City Mall opened with great fanfare. The Mall spanned an entire city block, a colossal 800,000-square-foot complex of enclosed retail, with five anchor department stores including J.C. Penney, Nordstrom, Weinstock’s (ZCMI), and The Bon Marché. On opening day “the crowd was beyond belief… wall-to-wall” as thousands of Ogdenites poured in to see the sleek climate-controlled galleria. Hopes ran high that the mall would “bring a renaissance to downtown” Ogden. And indeed, through the 1980s the City Mall was a regional draw and teenage hangout (even appearing as the backdrop of a 1987 Tiffany music video for the pop hit “I Think We’re Alone Now”, capturing its moment of glory).

Yet the mall’s success was short-lived. By the mid-1990s, Ogden City Mall began a steep decline. One by one its major anchors either closed or relocated to newer shopping hubs (Layton in particular had developed its own thriving mall and big-box corridor). The mall’s original private owner lost control to a bank, and more storefronts went vacant as shoppers’ preferences shifted. What was meant to save downtown instead became, in hindsight, an inward-facing “fortress” that stifled street life. Former Mayor Glenn Mecham later admitted the mall was “too fortresslike and not open enough” – its blank exterior walls literally turned their back on the rest of downtown. By 2001, Ogden’s leaders decided to cut their losses. The city bought out the failing mall – despite having “no firm plan” for the site’s future – and shut it down on January 1, 2002.

That spring, downtown Ogden witnessed a scene of cathartic destruction: wrecking crews tearing into the mall’s shell as a crowd of 100 onlookers cheered. “I have no sentimentality about them tearing down the mall,” declared Steve Dirks (who had returned as a city councilman), lauding the decision as “best for downtown”. The demolition, branded a “New Beginnings” event, symbolically cleared the way to reconnect the blocked streets and “go back to the past” – to an open-air, mixed-use city center resembling Ogden’s original downtown layout. Mayor Matthew Godfrey, a young and ambitious Ogden native, promised the replacement would be “a project our future generations can be proud of”. In place of the mall, Ogden in the mid-2000s built “The Junction,” a 20-acre entertainment and lifestyle complex with a multiplex cinema, indoor skydiving and climbing center, restaurants, shops, offices, and residences. Opened in phases by 2007, The Junction sought to re-create an urban feel rather than an isolated box. While its financial performance and heavy public subsidies drew some controversy, many credit The Junction with re-energizing downtown and sparking new businesses nearby. In essence, Ogden learned from its mall experiment: the future lay in embracing the city’s historic character and outdoor identity, not in copying suburban malls downtown.

All the while, Historic 25th Street’s preservation paid off. Through the ’80s and ’90s, even as the mall faltered, 25th Street continued attracting investment – often one quirky shop or restaurant at a time. The city created a 25th Street Historic District and redevelopment agency, narrowed the street to widen sidewalks, planted street trees, and installed retro streetlights. By 1981 “Two-Bit Street” was on the local historic register, and a merchants’ association formed to promote the area. Though Ogden’s overall economy struggled in the 1980s recession (which slowed many of the 1977 master plan’s goals), 25th Street gradually transformed. By the late ’90s it boasted fine-dining restaurants alongside antique stores, art galleries, a microbrewery, comedy club, and taverns, all in lovingly restored brick buildings. The street’s rough edges became part of its charm. Locals could point out the balcony from which a madam once dropped beans on potential customers below, or the alley once known as “Electric Alley” where bootleggers and brothels thrived – now marked with a historic plaque. This colorful past drew tourists off the interstate to stop and stroll “authentic” Ogden. By 2000, city planners proudly noted that 25th Street had “its own personality and character” intact amid downtown’s changes. In 2003, Ogden further enhanced downtown with a new amphitheater one block north of 25th, providing a venue for outdoor concerts, farmers’ markets and festivals. The historic heart of Ogden was beating again, just in a different rhythm than during the railroad heyday.

Reinvention in the 1990s: Higher Education and Base Conversions

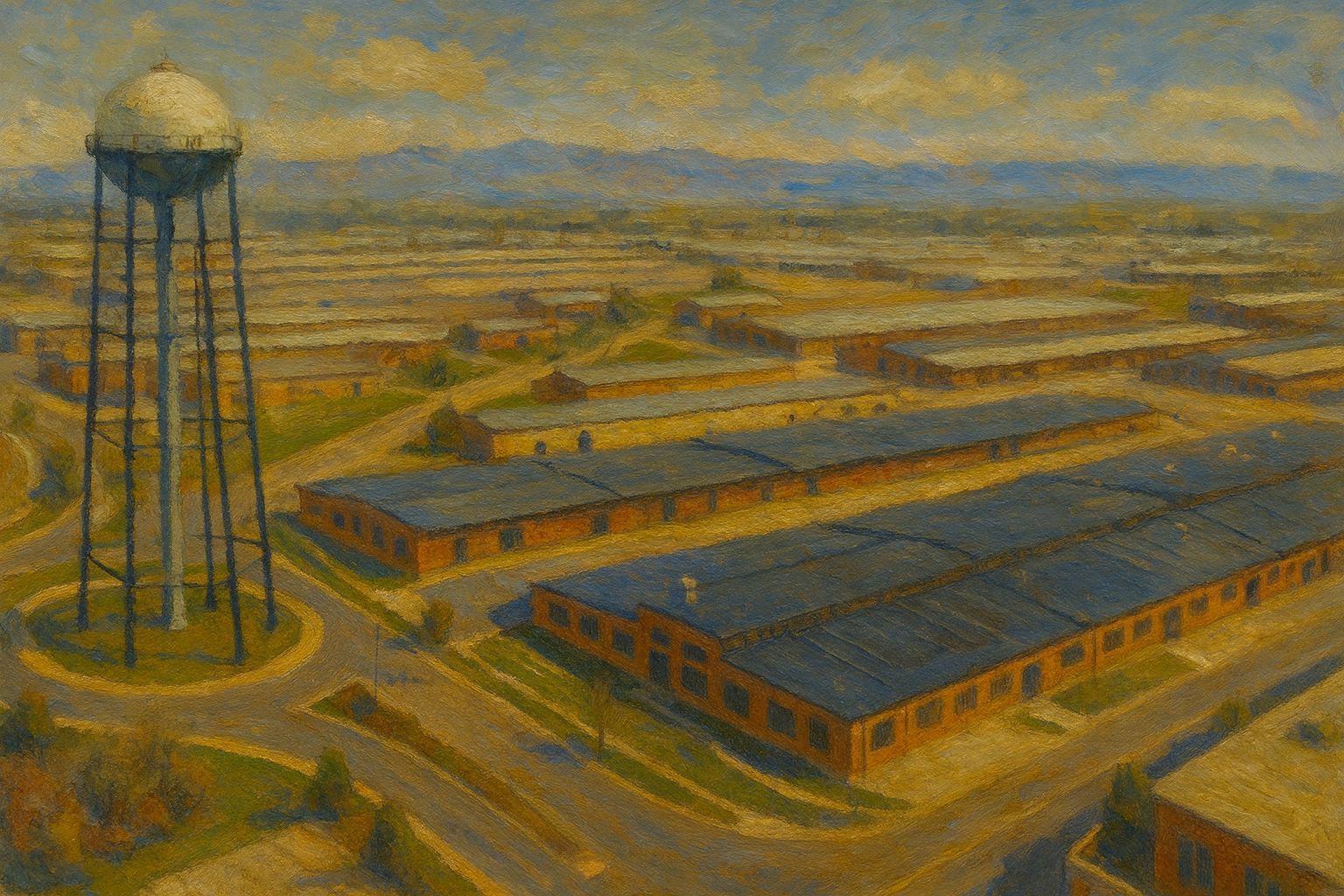

As the 20th century neared its end, Ogden faced economic crossroads beyond downtown retail. Manufacturing and defense – pillars of the local economy – were in flux. In 1995, the U.S. military delivered unwelcome news: Defense Depot Ogden (DDO), a huge military supply depot on Ogden’s west side, was slated for closure under a BRAC downsizing round. Since 1941, the Depot had employed thousands of civilians handling military food, clothing, and equipment shipments, and even housed Italian and German POWs during WWII. Losing the Depot threatened a major blow to jobs and city tax revenue. Ogden’s leaders scrambled to ensure this sprawling 1,100-acre site would not become a ghost town. Even before DDO officially closed in September 1997, the city formed a Local Redevelopment Authority to craft a reuse plan. The vision was to transform the former base into a private-sector business park, leveraging its warehouses, rail spurs and location. By 1999, Ogden struck a deal with a Salt Lake developer, The Boyer Company, to jointly develop and manage the property long-term.

The rebirth of the depot as “Business Depot Ogden” (BDO) was an immense undertaking – nearly a decade of environmental cleanup, re-zoning, and infrastructure upgrades. The federal government deeded the land and hundreds of old buildings to the city essentially for free. Ogden issued bonds for new roads and utilities, while freezing property taxes in the area so that any new tax revenue could be reinvested on-site. The adaptive reuse paid off: by the mid-2000s, BDO was humming with commercial activity, hosting manufacturers, warehouses, and even a large IRS data center on the grounds of the old depot. The local newspaper, the Standard-Examiner, relocated its headquarters and printing press to a renovated DDO building as one of the park’s first tenants. With over 6,000 employees and 125 businesses by 2006, BDO actually surpassed the depot’s Cold War employment levels, becoming a cornerstone of Ogden’s economy. The successful depot conversion also freed up prime real estate near downtown – hundreds of acres, once behind barbed wire, could be opened for future civilian development. It stands as one of Ogden’s great turnarounds: a symbol that the city could weather the loss of an old economy and build a new one.

Another key transformation was happening up on Ogden’s east bench: Weber State College was growing into a true university. Weber’s roots ran deep – founded as a small LDS academy in 1889 – but for decades it was a two-year junior college. In 1962, soon after moving to a new campus on the city’s southeast hillside, Weber gained four-year status and became Weber State College. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, the campus expanded rapidly, adding dormitories, a library, a new gym, and a science building. In 1978 Weber launched its first graduate program (a Master’s in Education), presaging more to come. The crowning milestone came on January 1, 1991, when Weber State College was officially renamed Weber State University. This change recognized Weber’s broadening mission – by then the school offered dozens of bachelor’s degrees and even a few master’s, anchoring it as northern Utah’s premier higher education institution.

Weber State’s growth injected fresh economic and cultural energy into Ogden. Student enrollment doubled in the 1980s to over 14,000, bringing youthful vibrancy (and not a few parking woes) to the city. The construction of the 12,000-seat Dee Events Center in 1977 gave Ogden a big venue for sports and concerts – and the WSU Wildcats rewarded fans with Cinderella runs in NCAA basketball tournaments (famously upsetting powerhouse teams in 1995 and 1999). By the late ’90s Weber State was reaching beyond Ogden: in 1997 it opened a new branch campus in neighboring Davis County. The WSU Davis campus in Layton enabled thousands of Davis County residents to attend college close to home, and further solidified Weber’s regional role. Indeed, Weber State and Ogden grew in tandem – the city often rallied around the university’s successes, and in turn Weber’s expansion of programs (from health professions to engineering) supplied the educated workforce local businesses needed. The campus also became a cultural hub for the community, with its theater productions, lecture series, and more. By 2002, Weber State had even produced its first Rhodes Scholar in decades – a sign of academic maturation. In short, the rise of Weber State University gave Ogden a new identity as a college town, not just a railroad or military town. As one local history put it, Ogden and Weber State “have a rich history of helping one another” – from the city’s citizens bailing out the college during the Depression, to the college returning the favor by fueling the city’s intellectual and economic life.

The 2002 Olympics and Ogden’s Outdoor Rebirth

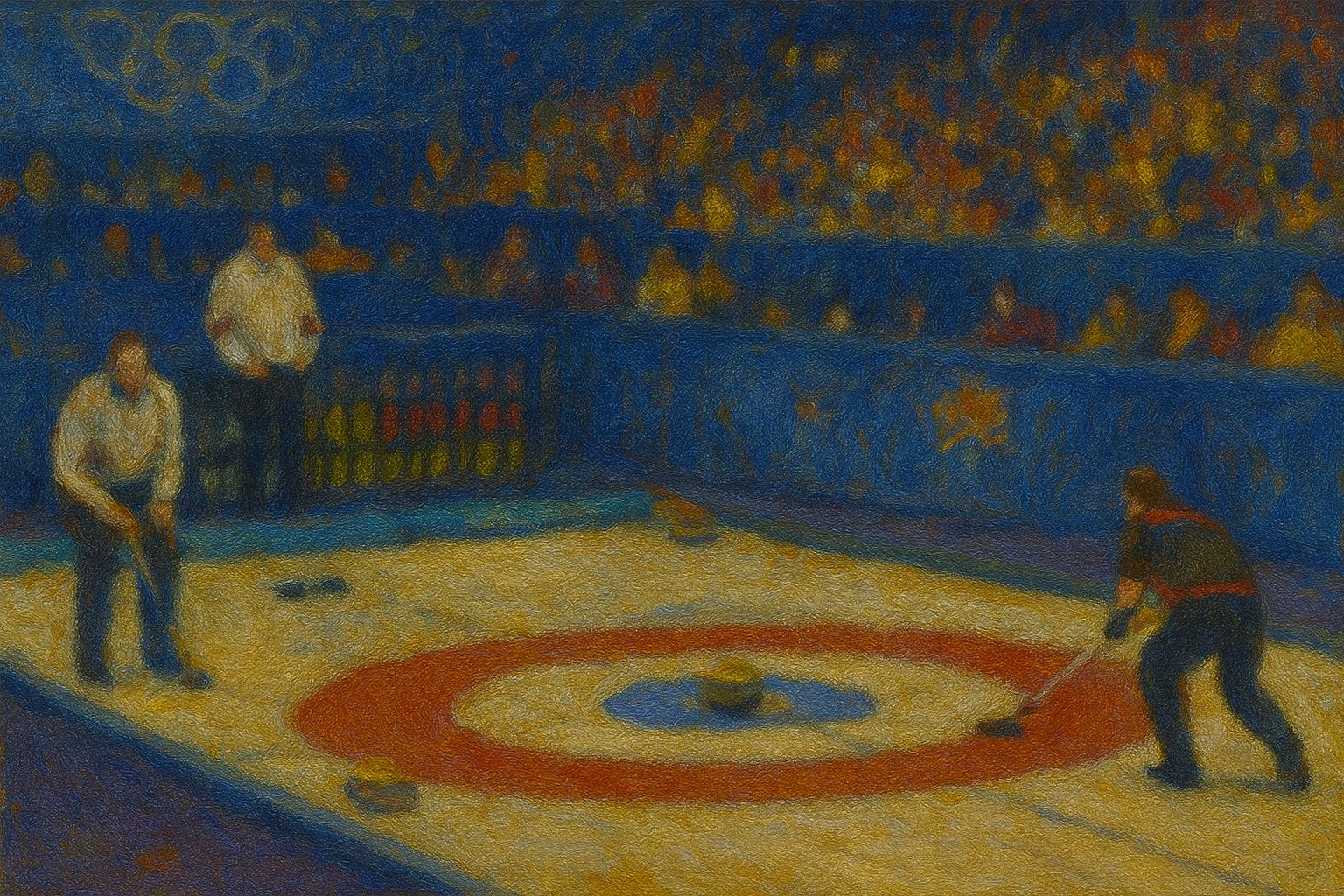

At the dawn of the 21st century, a global spotlight swept across northern Utah: the 2002 Winter Olympics. While Salt Lake City was the official host, Ogden found itself caught up in Olympic fever – and opportunity. Nearby Snowbasin Ski Area, just east of Ogden, was selected as the venue for the men’s and women’s downhill ski races, some of the Olympics’ marquee events. For Snowbasin, a rustic “locals’ mountain” with minimal facilities, this was a once-in-a-lifetime catalyst. Its owner, billionaire Earl Holding, poured investments into the resort ahead of the Games, determined to turn it into a world-class destination “to rival [his] Sun Valley resort in Idaho”. In the late 1990s crews built a brand new highway up to Snowbasin, replacing the old winding canyon road with a modern $16 million access road capable of moving thousands of spectators. Snowbasin itself became a massive construction zone: high-speed gondolas and chairlifts installed, state-of-the-art snowmaking systems covering the slopes, luxurious day lodges erected, and entire mountainsides regraded to meet Olympic standards. By Opening Day 2002, the once-sleepy ski hill had transformed into a premier four-season resort, reportedly at a cost of $70–90 million for the first phase alone. The Olympics also spurred a long-negotiated federal land swap that gave Holding 1,370 acres of U.S. Forest Service land at Snowbasin’s base – greenlighting his plans to add hotels, condos, and even a golf course in the future.

When the world’s fastest skiers finally plunged down Snowbasin’s Grizzly and Wildflower downhill courses in February 2002, Ogden cheered alongside the international audience. The spectacle not only put Ogden on the map for global visitors, it also seeded a new vision of the city as an “outdoor recreation” hub. In the Olympics’ wake, Ogden’s leaders – notably Mayor Godfrey – aggressively courted outdoor sports companies to set up shop in the area. And it worked: within a few years, a cluster of ski and outdoor gear firms relocated to Ogden, invigorating its economy. Amer Sports, the European parent of Atomic and Salomon skis, decided in 2006 to make Ogden its North American headquarters, after company execs fell in love with Utah during the Olympics. They were soon joined by others: Descente North America (ski apparel), Smith Optics, Geigerrig (hydration packs), and even the resurrected local ski brand Hart Ski all set up offices or design centers in Ogden. The city offered these companies renovated historic buildings (like the American Can Company factory-turned-outdoor campus) and the selling point of an outdoor lifestyle at the office doorstep. Where Ogden once recruited railroads and defense contractors, it now pitched itself as a Rocky Mountain basecamp for the outdoor industry. Over the next decade, this strategy would earn Ogden a reputation as an up-and-coming adventure town – but its genesis was in that post-Olympic confidence boost. As one state official observed a decade later, “the outdoor industry has thrived, particularly around Ogden” since 2002, helping Utah weather economic downturns by diversifying into recreation.

Ogden also benefited from Olympic-driven infrastructure beyond Snowbasin. Utah’s Olympic bid helped fast-track transportation projects, including the widening of I-15 through Weber and Davis counties and major transit investments. The most significant for Ogden was the development of UTA’s FrontRunner commuter rail, fulfilling a dream long on the region’s wish list. FrontRunner was conceived as a high-speed commuter train connecting Weber, Davis, and Salt Lake counties – essentially reviving rail transit along the Wasatch Front. Planning accelerated in the early 2000s, and Ogden eagerly positioned itself as the northern terminus. In fact, as early as 2000, city planners were working to locate a new intermodal transit hub next to Union Station, hoping to tie commuter rail, buses, and historic 25th Street together. “We want to encourage people to come downtown, and 25th Street is part of that,” deputy planning director Richard McConkie explained, emphasizing that the station area would be key to Ogden’s revival.

By April 2008, the vision became reality: FrontRunner trains began rolling between Salt Lake City and Ogden, restoring passenger rail service (of a modern sort) to Ogden for the first time since the Pioneer’s 1997 farewell. Ogden’s new commuter rail station – just north of the old Union Station – opened as a sleek, park-and-ride friendly hub for daily riders. (Sadly, efforts to route the trains directly into the historic Union Station proved too complex, so the grand depot remains a museum-only facility for now.) Nonetheless, FrontRunner marked a profound shift: Ogden was reconnected by rail to the rest of the metro region, this time not as a junction for cross-country travelers, but as a commuter link carrying workers to and from jobs in Salt Lake City and beyond. Coupled with expanded bus service and plans for streetcar or BRT lines, it signaled that transit was back in the Crossroads of the West – an echo of the past, updated for a new century. The commute between Ogden and Salt Lake, once mainly by highway, now could be a relaxing train ride, and transit-oriented development began springing up near the Ogden station in subsequent years. It was a fitting coda to Ogden’s transformation: after decades of car-centric growth, the region was rediscovering the benefits of rail in a modern context.

Ogden’s Resilience and Renewal

Over the four decades from the 1960s to the 2000s, Ogden, Utah underwent a remarkable metamorphosis. The city that entered the 1960s was a railroad titan beginning to creak, a defense-dependent economy, and a place grappling with social change as traditional industries faded. By the early 2000s, Ogden had re-emerged with a diversified identity: a historic downtown celebrated for its character, a tech-infused business park on former military land, a thriving university on the hill, and a growing reputation as an outdoor recreation mecca. This journey was far from smooth – there were false starts and hard lessons (the failed mall being one vivid example). Yet the city’s narrative arc is one of resilience and reinvention.

Characters and anecdotes from each era live on in local memory: The last stationmaster at Union Station locking up the waiting room after Amtrak pulled out in ’97; “Rose” the flamboyant madam strolling 25th Street with her pet ocelot in earlier days; crowds packing the Ogden City Mall in 1980 to glimpse its glitzy atrium, and a different crowd two decades later cheering as its walls came down. There’s the scrappy Weber State student body doubling and turning a commuter college into a university powerhouse. And the unlikely sight of Olympic skiers racing down Mt. Ogden, as locals watched with pride – followed by global ski companies deciding that if it’s good enough for the Olympics, it’s good enough for us, and setting up shop in Ogden. Each of these moments marks a turning point in Ogden’s story.

Surrounding communities shared in this evolution. Layton grew from a tiny farm town into a major suburb with its own mall and regional hospital. Clearfield and Roy became home bases for Hill AFB civilian workers, while the old Clearfield depot’s rebirth as Freeport Center proved a model of post-military reuse decades before Ogden’s BDO. Davis County in general transitioned, as one county history puts it, “from rural to residential to office/retail”, becoming far more diverse in the process. By 2000, Davis County was touted as having “a wide mix of people” of many ethnic and cultural backgrounds – a striking change from its pioneer homogeneity. Ogden itself, historically one of Utah’s more diverse cities (thanks to its railroad and military heritage), saw its Hispanic population and other communities grow, adding new cultural richness to local life. Old institutions like the Defense Depot closed, but new ones like BDO and the expanded Weber State carried the torch forward.

Through all this, Ogden never lost sight of its past – even as it pushed toward the future. The majestic Union Station still anchors the west end of 25th Street, lovingly maintained as a museum where you can see vintage locomotives and exhibits about the city’s boomtown railroad days. Historic 25th Street today bustles with cafés, art festivals, and farmers’ markets, yet you can still duck into a 19th-century saloon building and feel echoes of the rowdy Junction City of old. Ogden’s transformation has been one of addition, not erasure: adding new dimensions (education, outdoor recreation, high-tech industry) while retaining the unique history and community spirit that make Ogden Ogden.

As the city moved into the 21st century, it did so with hard-earned confidence. The trials and triumphs from the 1960s through 2000s taught Ogden that it could adapt and thrive. From the end of the railroad era to the dawn of the commuter rail era, from “Two-Bit Street” to “Great American Main Street,” from military depot to business park, the story of late-20th-century Ogden is ultimately a story of renewal. Mayor Godfrey, reflecting on the changes, encapsulated it well: Ogden had to reinvent itself by leveraging what made it special – its history, its mountains, its people – and by not being afraid to embrace bold ideas while honoring the past. Today’s Ogden is a testament to that journey – a city continually pulsing with new energy each Friday night on Historic 25th, even as the trains no longer run. The junctions now are cultural and economic rather than just steel rails, but Ogden remains, at heart, the Crossroads of the West in its own ever-evolving way.

NOTES FROM THE HORSE

“Neigh.”

Until next time,

Raw, weird, and local.