Previously On “Ogden”

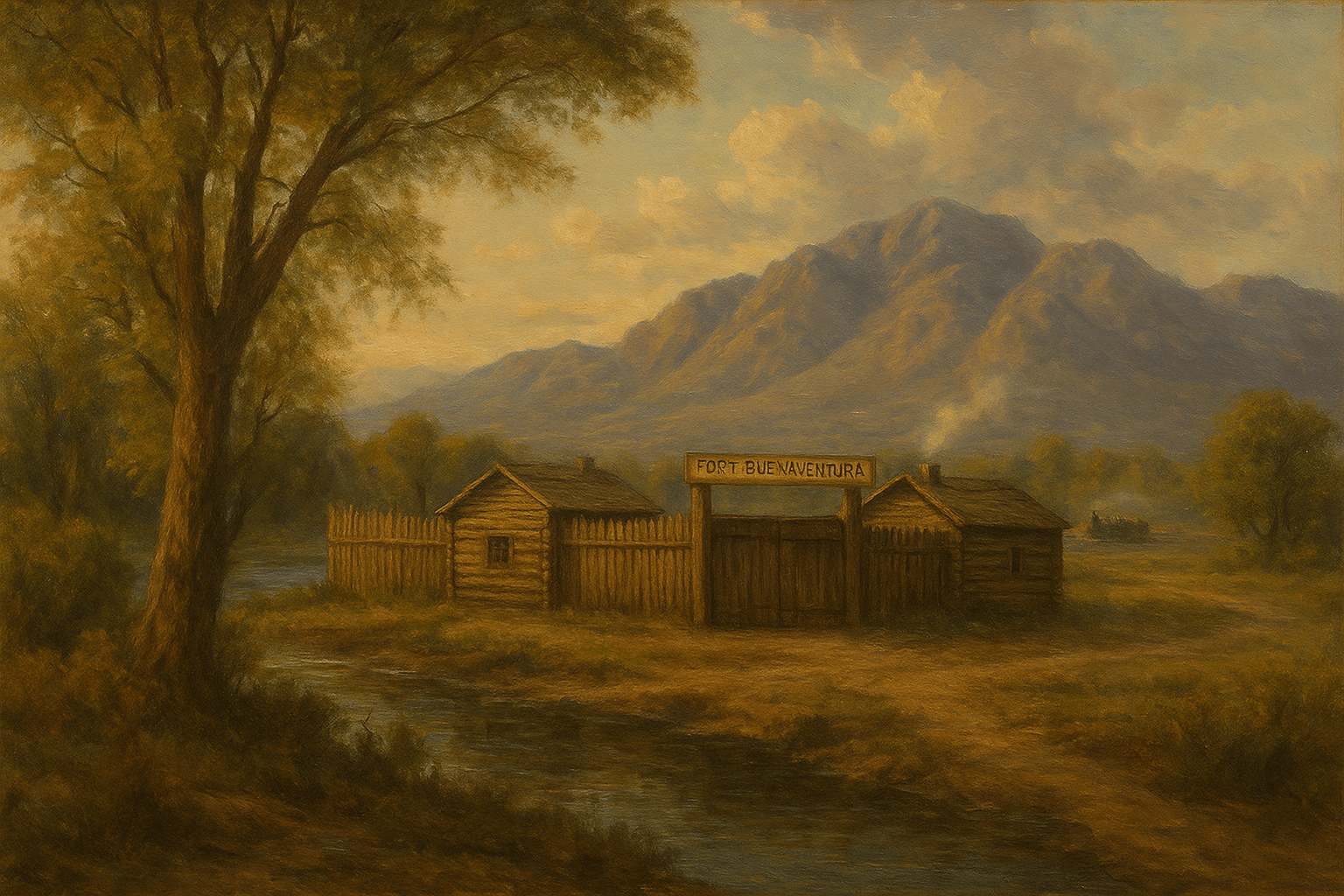

Long before it was a bustling railroad hub, Ogden began as a remote trading outpost. In 1845, trapper Miles Goodyear built a small stockade called Fort Buenaventura near the Weber River – the first permanent European-American settlement in what is now Utah. Goodyear’s fort and claim (covering much of today’s Weber County) were purchased in 1847 by Mormon pioneers led by Captain James Brown (using gold coin earned from the Mormon Battalion). That winter and the following spring, Brown and Lorin Farr (an early LDS leader) settled with their families at the fort, soon nicknamed Brown’s Fort. By 1851 the growing farm village was incorporated as Ogden City, named after Peter Skene Ogden, a Hudson’s Bay Company trapper who had scouted the area decades earlier. Ogden at this time was a modest, agrarian Mormon community hugging the banks of the Weber and Ogden rivers. Water from mountain streams limited how much the colony could expand its irrigated fields. Still, the town slowly grew – from about 1,100 residents in 1851 to around 1,463 by 1860 – supporting a new LDS tabernacle (finished 1869) and a grid of log and adobe homes. Isolated from the outside world by hundreds of miles of frontier, mid-19th-century Ogden was a “truly a frontier town” – its unpaved streets alternated between dust and mud, with a few plank sidewalks in front of stores and saloons. During the 1857–58 Utah War, Ogden briefly emptied when LDS residents fled south, but they soon returned to resume their quiet life of farming and trading. Little did those early settlers suspect that their sleepy outpost was on the verge of dramatic changes that would put Ogden on the national map.

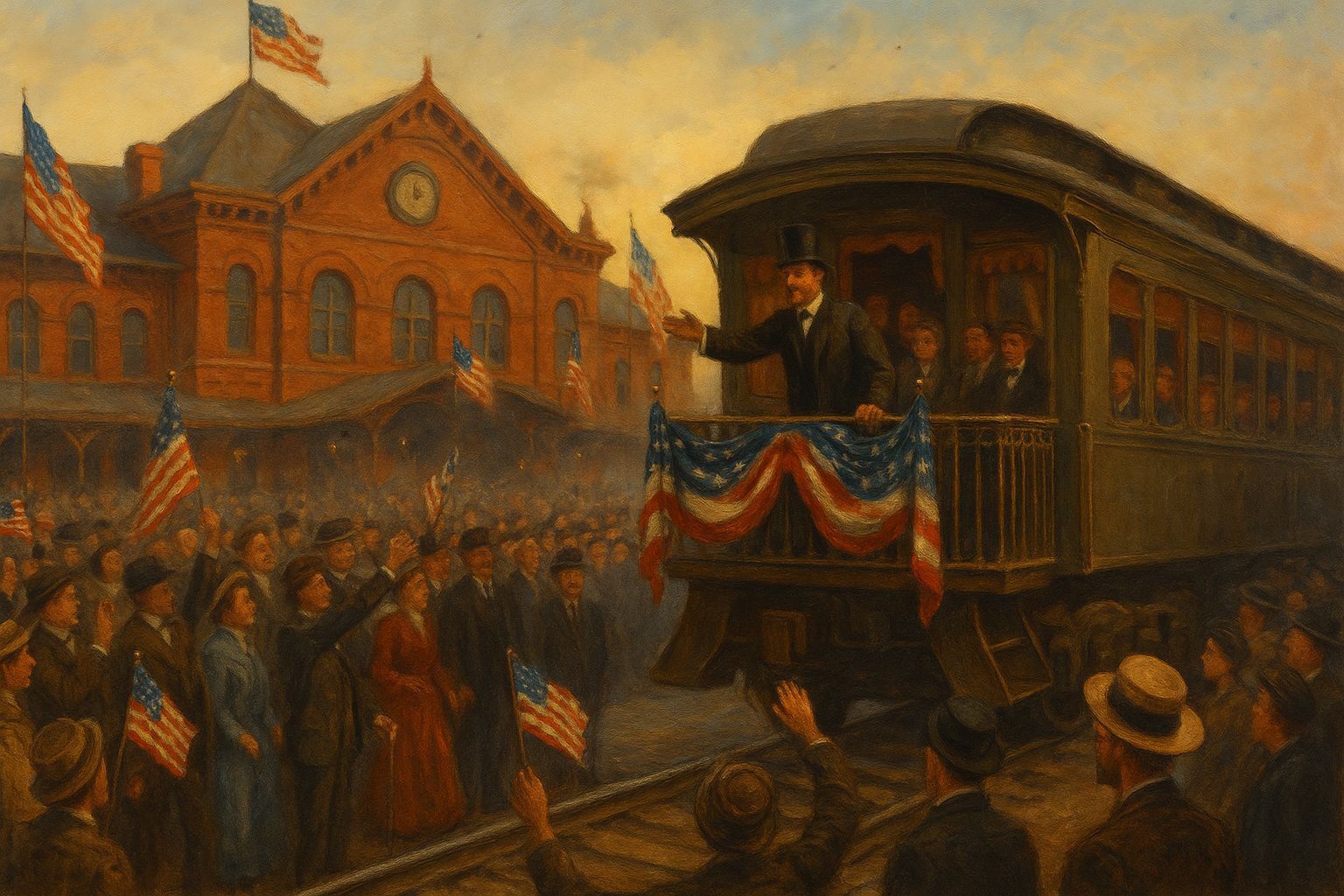

The turning point in Ogden’s history came in 1869 with the completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad across the continent. On May 10, 1869, the symbolic golden spike was driven at Promontory Summit – just 53 miles northwest of Ogden – linking the Union Pacific and Central Pacific lines. Almost overnight, Ogden transformed from a rural backwater into a strategic crossroads of the American West. Brigham Young and other Mormon leaders maneuvered to ensure Ogden became the junction point for the two railroads, thwarting an attempt by non-Mormon businessmen to make the gentile town of Corinne the main hub. Their plan succeeded: by 1874 the UP and CP agreed to designate Ogden as the primary terminal, and competing Corinne’s commercial hopes collapsed. Ogden’s Chamber of Commerce proudly adopted the motto “You can’t get anywhere without coming to Ogden,” reflecting the city’s pivotal location on both east–west and north–south rail routes. Indeed, travelers heading to California from the eastern U.S. typically passed through Ogden (often bypassing Salt Lake City), and soon “Junction City” became a common moniker for the town.

The Impact

The impact of the railroad on Ogden’s growth was immediate and profound. In 1868, Ogden was still a small town; by 1870 (just one year after the rails arrived) its population had more than doubled to over 3,100. Newcomers poured in: not only Mormon converts arriving by train (a far easier journey than handcarts and ox-drawn wagons), but also railway laborers, merchants, adventurers, and fortune-seekers from across the United States and abroad. During the 1870s, Ogden developed into a major transportation and commerce center. The railyards and Union Depot (first built in 1869) bustled with activity. A visitor in this era described the remarkable scene at train time: “amongst [the passengers] one would see blue-coated U.S. Army officers and soldiers; mining men and prospectors; long-haired, buckskin-clad mountaineers and trappers; red-blanketed Native Americans from the north and west; Chinese laborers wearing broad bamboo hats; well-dressed travelers from Eastern cities bound for California; and even aristocratic English, French, Dutch, and German tourists on their way via San Francisco to China, Japan, New Zealand, or Australia.” Ogden had truly become, as one journalist put it, a “melting pot cosmopolitan mecca” where people from all corners of the world rubbed shoulders on the station platforms.

As trade and traffic increased, industries and businesses flourished. During the late 1870s and 1880s, Ogden’s economy diversified far beyond subsistence farming. The city’s boosters nicknamed it the “Crossroads of the West,” and it was soon threatening to overshadow even Salt Lake City as Utah’s commercial capital. Railroads became the region’s largest employers (by the early 1900s, nine different rail companies had terminals in Ogden). Factories, shipping warehouses, and shops sprang up to meet the needs of travelers and residents alike. Woolen mills, flour mills, canneries, breweries, iron works, stockyards, banks, hotels – all were established during this boom period. Local entrepreneurs made fortunes in commerce and manufacturing. For example, businessman Fred J. Kiesel ran a major mercantile house, the Kuhn brothers opened thriving retail and banking ventures, and Scottish-born industrialist David Eccles founded enterprises like the Amalgamated Sugar Company and several Ogden banks. The Wattis brothers (Edmund, William, etc.) and Thomas D. Dee started Utah Construction Company in Ogden, which grew into a nationally significant construction firm. In a modest workshop on Ogden’s Washington Boulevard, young John Moses Browning began designing firearms in the late 1870s – securing his first gun patent in 1879 – and would soon revolutionize the firearms industry worldwide. Meanwhile, local farmers benefited from rail access to new markets: Ogden’s produce (from vegetables to fruit from nearby orchards) could be loaded on trains and shipped to distant cities, bringing new prosperity to the region. By the 1880s, the once-sleepy town had the air of a boom city. Ogden’s population reached 6,069 in 1880 and then nearly 13,000 by 1890, doubling with each decade. One contemporary observer noted that “Ogden stirred eagerly to the new blood in its veins” as railroads and commerce turned it into “a bustling Wild West frontier town” unlike any other in Utah.

Cultural Dynamism and “Devil’s Playground”

With the influx of outsiders after 1869, Ogden became one of the most diverse communities in the Intermountain West – a distinction that set it apart sharply from other Utah towns. As early as the 1870s, a strong admixture of non-Mormons (“Gentiles”) had settled in Ogden alongside the majority LDS population. This created immediate challenges – and opportunities – for coexistence. Many longtime Mormon residents retained vivid memories of past conflicts with “gentiles” and eyed the newcomers warily, while some non-Mormon arrivals came imbued with a “crusading zeal” to “settle the Mormon problem” (fueled by lurid national reports of polygamy and theocracy in Utah). Tensions did arise – for instance, gentile politicians and businessmen initially tried to wrest local control from LDS leaders, and at one point federal marshals enforced anti-polygamy laws in the region. Yet, Ogden largely avoided the open sectarian strife seen in Salt Lake City during the 1870s and ’80s. In fact, observers noted that “a balance of toleration was quickly struck in Ogden,” and the old Mormon-Gentile antagonism “somewhat disappeared” – especially in the business arena, where cooperation proved more useful than conflict. A symbol of this new era came in 1889, when Fred J. Kiesel – a prominent non-Mormon merchant – was elected Mayor of Ogden, becoming the first Gentile mayor in Utah history. This breakthrough in a state long dominated by LDS leadership showed how far Ogden had come: Mormons and non-Mormons were literally sharing power in the “Junction City.” “Sooner than any other major Utah city, Ogden had to face the problem of reconciling these two factions,” wrote historian Dale Morgan, noting that Ogden’s mix of people forced a pragmatic harmony.

Beyond the Mormon/Gentile divide, Ogden in the late 19th century was a true cultural crossroads, home to a rich patchwork of ethnic and racial communities. The railroad imported waves of immigrant labor – and when the work was done, many stayed. By 1890, a significant share of Ogden’s population was foreign-born, including large numbers of Irish, German, Scandinavian, and English immigrants (many of the latter two came as Mormon converts). Dozens of Chinese workers who had helped build the Central Pacific line also settled in Ogden, establishing a small Chinatown near the rail yards. Census records show the Chinese population in Ogden rose from just 33 people in 1880 to over 100 by 1890. A “Chinese quarter” developed along lower 25th Street, “from the Broom Hotel to the railroad station,” filled with wooden shanties housing Chinese laundries, tea shops and lodging houses. One early resident described rows of low wooden buildings on 25th Street where “many of these establishments were operated by the Chinese.” The Chinese community made its living largely through running laundries (Ching Wah’s laundry on Grant Ave., Sam Wah’s on 25th St., etc.) and small import shops. They also maintained cultural traditions – occasionally holding Chinese New Year celebrations that drew curiosity from Ogden’s populace. (According to one account, in the 1890s Ogden’s Chinese New Year festivities saw local police chiefs and dignitaries invited to feasts, and elderly Chinese gentlemen handing out red “lucky money” envelopes to American children.) Despite this goodwill, prejudice was never far: anti-Chinese sentiment ran high across the West in the 1880s, and Ogden was no exception. The local Ogden Junction newspaper railed against the “inferior and alien race” taking white men’s jobs, and federal Chinese Exclusion laws curtailed further immigration. Nevertheless, the Chinese community of Ogden endured into the next century (only fading as railroad jobs dried up), leaving an indelible mark on the city’s character.

Ogden also became home to one of Utah’s earliest Black communities. After the railroad arrived, many African Americans came West to work as Pullman porters, cooks, and laborers on the trains. The Southern Pacific and Union Pacific lines employed numerous Black staff, making Ogden a frequent layover point for Black railroad workers – and the largest Black population in Utah outside Salt Lake City for many decades. Barred from most white establishments and neighborhoods by custom (and often formal covenants), Black Ogden residents formed a tight-knit neighborhood between 24th and 30th Streets west of Washington Ave. By the 1890s they had founded their own churches and social clubs. In 1890, Black Ogdenites organized the Wall (Street) Avenue Baptist Church, one of the first Black-led congregations in Utah. Black-owned businesses – barber shops, cafés – clustered near 25th Street, serving both Black clientele and others. Though small in number, Ogden’s African American pioneers built a supportive community in the face of the era’s racial discrimination, adding yet another thread to Ogden’s human tapestry.

Equally notable was the city’s religious pluralism by the turn of the century. While LDS (Mormon) congregations remained the majority (Ogden was the seat of the Weber Stake, with a large tabernacle on Tabernacle Square), the influx of outsiders brought a variety of faiths to town. Catholic services began by 1871, when Father Patrick Walsh traveled up from Salt Lake City to hold Ogden’s first Mass in a local home. A humble wooden St. Joseph’s Catholic Church was soon built on 25th Street to serve Ogden’s growing Irish Catholic population. Fundraising for that first chapel was a community affair: a grand church fair in 1877 drew “Catholics, Mormons, Protestants, Jews, Gentiles, and aristocratic Chinamen of those times” all together to contribute. By 1884, the Catholic community in Ogden numbered around 400, and in 1889 they purchased land for the larger St. Joseph’s church that stands today (completed in 1902). Protestant denominations also took root early. Methodists held Ogden’s first Protestant sermon in 1870 at the railroad depot and built a permanent church on 24th Street by 1870–71. The Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd was erected in 1874 on the corner of 24th and Grant, funded by an Eastern donor and serving a congregation of railroad workers and other non-LDS locals. Presbyterians and Congregationalists followed in the 1880s, establishing churches and missions in Ogden (the First Presbyterian Church would open a substantial stone building in 1906). Even Jewish settlers were present in Ogden – a handful of Jewish merchants and their families lived in the city by the 1880s, some participating in social life (as evidenced by the mention of “Jews” among those at the 1877 church fair). This coexistence of multiple religions was quite unique in Utah at the time, when many smaller towns were almost exclusively Mormon. In Ogden, however, a traveler in 1890 could find a Mormon sacrament meeting, a Catholic Mass, and a Protestant service all taking place on a given Sunday within blocks of each other. The necessity of living side by side fostered a level of interfaith tolerance – and a cosmopolitan atmosphere – that distinguished Ogden from other Utah communities.

Of course, not all of Ogden’s newfound vibrancy was genteel. The same factors that made Ogden prosperous – constant train traffic, an uprooted transient population, economic opportunity – also gave it a rowdy, rough-edged reputation that became legendary. Nowhere was this more evident than on 25th Street, the three-block stretch between Union Station and Washington Boulevard. During the late 19th century, 25th Street transformed into Ogden’s notorious vice district, earning nicknames like “Notorious Two-Bit Street” and “the most sinful street in America.” Legitimate businesses – hotels, restaurants, clothiers – lined the street, but so did a shadow world of gambling halls, saloons, brothels and opium dens that catered to rail travelers and locals alike. By the 1880s, as one history notes, “the street became known for corruption and immorality”. Western lawmen, outlaws, cowboys, and drifters could all be found blowing off steam on 25th Street. Gunfights and drunken brawls occasionally broke out, and certain establishments were reputed to offer every indulgence for the right price. Union Station acted as a funnel for all this human drama – and as the first thing rail passengers saw stepping into Ogden. One popular legend claims Al Capone later quipped that Ogden was too wild a town even for him, and indeed the city’s seedy underbelly persisted into the Prohibition era (when 25th Street bootleggers dug secret tunnels to move liquor). But around 1900, this “Wild West” character was already well established. Ogden was a city where frontier virtue and vice coexisted: temperance societies and church socials on one corner, gambling and “houses of ill repute” on the next. This dynamic – a conservative Mormon heritage colliding with the freewheeling ethos of a railroad boomtown – defined Ogden’s personality and set it apart from stricter, more homogenous Utah towns. Locals learned to take a pragmatic approach: as long as the city prospered, a little chaos on 25th Street was tolerated. In the words of one resident, Ogden “had to learn to coexist” with itself – to reconcile pious pioneers and gun-toting gamblers, the choir and the cabaret under the same skyline. That uneasy coexistence (and the colorful tales that came with it) would remain part of Ogden’s identity well into the next century.

On the National Stage

As the 19th century drew to a close, Ogden had firmly established itself as one of the West’s important hubs. It was now Utah’s second-largest city (nearly 16,000 people by 1900, trailing only Salt Lake City) and in some ways its most famous. The city’s role as the “Crossroads of the Continent” made it nationally known. Every day, multiple transcontinental trains stopped in Ogden – by the 1890s, over 100 rail cars passed through daily – bringing visitors and dignitaries. U.S. Presidents and other VIPs routinely came through Ogden on whistle-stop tours. (It’s recorded that President Theodore Roosevelt rode along 25th Street in a parade; later, Presidents William H. Taft and Herbert Hoover also visited Ogden, and world-famous showman “Buffalo Bill” Cody brought his Wild West show to town – all testament to Ogden’s status as a significant stopover.) Ogden’s businessmen and civic leaders ambitiously promoted their city on the national stage. In 1890, resident William “Coin” Harvey – a flamboyant advocate of free silver coinage – organized an elaborate “Ogden Carnival” intended to lure investors, tourists, and new settlers. The carnival featured parades, exhibitions, and fanfare to showcase Ogden’s opportunities. “Great boom at Ogden!” blared some advertisements. Although Harvey’s boosterism didn’t spark the big real-estate boom he hoped (and he soon left town to pursue a quixotic U.S. presidential run), it reflected the optimism and swagger in Ogden at the end of the 1800s. This was a city confident in its rise: some locals even whispered that Ogden might overtake Salt Lake City as Utah’s economic center in the new century.

By 1900, observers could look at Ogden and see the results of 50 years of dramatic transformation. What began as forty or fifty pioneer families huddled in a riverside fort had grown into a bustling railroad metropolis with electric streetcars, telegraph lines, elegant brick hotels, opera houses, and a mix of cultures rivaling cities many times its size. An Ogden editorial proudly noted that “commerce houses, factories and spires of many faiths now pierce the sky where once stood only wagons and cabins”. The city’s ascension was not without growing pains – but those struggles became part of its unique story. Ogden’s diversity, its blend of sacred and profane, and its pivotal role in connecting East and West made it a true crossroads city. As one historian aptly said, “Ogden was growing on a national stage” in the late 19th century, a microcosm of the American West’s transition from frontier to modernity.

Legacy and Preservation

The echoes of Ogden’s 19th-century ascension are still visible today, and preserving this heritage has become a community priority. Many historic structures and sites from the era still exist and merit preservation efforts. For example, Fort Buenaventura Park now marks the site of Miles Goodyear’s original 1845 fort – a tangible reminder of Utah’s earliest settlement. In downtown Ogden, the Lower 25th Street Historic District has one of the most intact collections of turn-of-the-century commercial architecture in the state. Strolling these three blocks, one can see dozens of restored late-1800s brick buildings that once housed the saloons, hotels and shops of Ogden’s glory days. (In fact, 25th Street’s architectural continuity earned it a place on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978 and the moniker “Notorious Two-Bit Street” is now a point of pride.) At the west end of 25th stands Ogden Union Station, the grand train depot (rebuilt in 1924 after a fire) which today operates as a museum – home to the Utah State Railroad Museum and a gallery of vintage locomotives – as well as the John M. Browning Firearms Museum, celebrating the local inventor’s legacy. Nearby, the imposing Bigelow Hotel, originally founded by 1891 (and later rebuilt in 1927), still towers as a landmark of Ogden’s early hospitality industry.

Equally important are Ogden’s historic religious and civic buildings that survived. The Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd (built 1874) still stands on its original corner, its Gothic Revival stonework recalling the railroad-era congregation that built it. A few blocks away, the St. Joseph’s Catholic Church built in 1902 continues to serve parishioners, its stained-glass windows and Victorian Gothic design a direct link to the Irish railroad workers who helped establish Catholicism in Ogden. Perhaps most special is the Ogden Relief Society Hall, a red-brick Gothic meeting hall on 21st Street that was commissioned by Brigham Young in 1877 as a place for the LDS women’s organization. Completed in 1902 and funded by pioneer women who saved pennies from egg and butter sales, this building is the only Relief Society hall of its kind ever built. It quickly became a social center hosting “festivals, plays, concerts, dances, etc.” for the whole community. Miraculously, the Relief Society Hall still stands today (now housing the Daughters of Utah Pioneers Museum), representing the spirit of cooperation and community of early Ogden. Preserving such landmarks is vital, as they anchor the stories of Ogden’s past in the present-day cityscape.

In Ogden, history is not forgotten – it’s etched into the very layout of the streets and the walls of century-old buildings. The city’s dynamic 19th-century rise, fueled by railroads and tempered by the meeting of many peoples, gave Ogden a heritage that is both unique in Utah and nationally significant. It’s a heritage of trailblazers and train whistles; of pioneer fortitude and railroad ambition; of Mormon farmers, Chinese laundrymen, Irish miners, Black porters, and frontier lawmen – all learning to coexist in one community. This legacy makes modern Ogden a living museum of Western history. As preservationists often point out, protecting Ogden’s historic sites is not just about bricks and mortar, but about honoring the human stories – the triumphs, conflicts, and compromises – that unfolded here. The contrast of cultures and the spirit of tolerance that developed in 19th-century Ogden truly makes Ogden different and stand out. By understanding and preserving this rich past, we ensure that Ogden’s extraordinary ascension from a lone fort to a “Junction City” of the West continues to inspire future generations.

NOTES FROM THE HORSE

“Neigh.”

Until next time,

Raw, weird, and local.