In the span of just two decades, Ogden underwent a dramatic metamorphosis. The 1930s found this railroad junction city reeling from the Great Depression, its once-bustling commerce slowed to a crawl. By the 1940s, world war had utterly reshaped Ogden into a vital military logistics hub – a boomtown teeming with workers, soldiers, and round-the-clock trains. And as the 1950s dawned, Ogden again reinvented itself, shedding a notorious vice-fueled reputation in favor of suburban respectability. Today we’ll explore how big-picture forces – economic collapse, world war mobilization, and postwar prosperity – intertwined with the colorful local character that defined Ogden’s evolution from the Depression through the postwar era.

Hard Times on Two-Bit Street: Ogden in the 1930s

In the early 1930s, Ogden’s fortunes hit rock bottom. The prosperous railroad and commercial activity of earlier decades had slowed by the late 1920s, and the Great Depression brought “bad economic times” to the city. Unemployment in Utah soared to catastrophic levels – roughly 36% of the labor force was jobless at the Depression’s peak, far above the national average. Ogden was not spared: long breadlines and shuttered businesses became familiar sights downtown, and the once-booming railyards grew quiet. With legitimate jobs scarce, the city’s infamous 25th Street – nicknamed “Two-Bit Street” – leaned into its outlaw reputation. During Prohibition (which hit Utah in 1917, even earlier than nationwide), Ogden had already been a “rough-and-tumble” haven of speakeasies, gambling dens, opium dens, and brothels. When Prohibition ended in 1933, bootlegging waned, but organized crime simply refocused on illicit gambling and prostitution. With train traffic and trade depressed, Ogden’s economy in the ’30s became disproportionately reliant on vice as a source of activity.

Yet even amid the hardships, glimmers of resilience appeared. Federal New Deal projects brought a modest infusion of jobs and infrastructure. In 1934, construction began on Pineview Dam in Ogden Canyon as part of an irrigation project, and by 1937 Ogden celebrated the opening of a splendid new Ogden High School, an Art Deco showpiece funded by the Public Works Administration. Dubbed Utah’s “million dollar school,” its construction created desperately needed work for “hundreds of workers” and boosted local morale. At the same time, civic boosters in Ogden were eyeing an even bigger lifeline: the rising drumbeat of war in the late 1930s. The Ogden Chamber of Commerce aggressively lobbied federal authorities to locate defense installations in the area as a way to jolt the economy back to life. One early success was reactivation of the Ogden Arsenal (an Army munitions depot west of town). Largely mothballed after World War I, the arsenal got a New Deal-funded upgrade in 1935–38, with the Works Progress Administration building a new ammunition plant there. This effort paid off: by 1938 the arsenal was hiring again, and when war broke out it would explode to over 6,000 civilian workers by 1943 churning out bombs, shells, and small arms. The groundwork was being laid for Ogden’s wartime revival.

“Keep ’Em Flying”: Ogden’s War Boom in the 1940s

The 1940s brought Ogden a whirlwind of change. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States’ entry into World War II transformed Ogden virtually overnight into a key military logistics and transportation hub. Long before the war’s end, locals were calling it the “Crossroads of the West” once again – this time not for pioneers or commerce, but for the vast movement of troops and materiel bound for global battlefields.

Even before the U.S. formally entered WWII, defense investment poured into the Ogden area. In January 1940, construction began on a major Army Air Corps supply and maintenance depot on a patch of Davis County farmland just south of Ogden. This facility, originally called Hill Field (later Hill Air Force Base), was chosen thanks to Ogden’s strategic advantages: a “safe interior section of the country with easy access to transportation” by rail and road. The Ogden Chamber had helped land the project by donating land and emphasizing that the city lay safely inland, yet well-connected to West Coast ports. Hill Field’s growth was explosive. By 1943, “Hill Field was the largest employer in Utah”, with 15,000 civilian workers and 6,000 military personnel on base – a massive operation dedicated to repairing aircraft, overhauling engines and radios, and keeping America’s warplanes ready to “Keep ’Em Flying”. The base even utilized Italian and German POWs as laborers, as did other local facilities, further swelling its workforce.

Hill Field was just one part of a constellation of war facilities that sprang up around Ogden. In 1942 the U.S. Navy opened the Clearfield Naval Supply Depot on former farmland just south of Ogden. This sprawling inland port supplied the Pacific Fleet and soon boasted nearly 8,000 civilian employees, with warehouses covering almost 8 million square feet. By 1944, Clearfield was receiving 2.5 million tons of military goods (in 31,000 railroad boxcars) per year and shipping out half that amount in an “around-the-clock operation.” In fact, the inventory stored at Clearfield during the war – from uniforms and spare parts to hospital equipment – was valued at roughly three times the entire assessed property value of the state of Utah, a statistic that boggles the mind. Meanwhile, the Army in 1941 established the Utah General Depot on Ogden’s west side (locally called the “Second Street” depot, later renamed Defense Depot Ogden). This quartermaster depot handled everything an army might need except weaponry, making Ogden a primary funnel for supplies to overseas forces. It soon earned the distinction of being “the largest quartermaster depot in the United States” during WWII, employing about 4,000 civilians alongside 5,000 German and Italian POWs who were put to work there. Each day during the peak war years, the Ogden depot loaded some 200 railcars with food, clothing, medical supplies, fuel, and equipment – out-shipping the three other major Utah depots combined. Ogden also became administrative home to agencies like the U.S. Forest Service’s regional office (moved to Ogden during the war). Virtually overnight, this once-sleepy city found itself awash in federal money and jobs. Wartime spending injected unprecedented prosperity: thousands of locals found work building or staffing the new bases, and thousands more workers flooded in from elsewhere seeking a paycheck. By 1943, unemployment was essentially wiped out – a far cry from the grim days of a decade earlier.

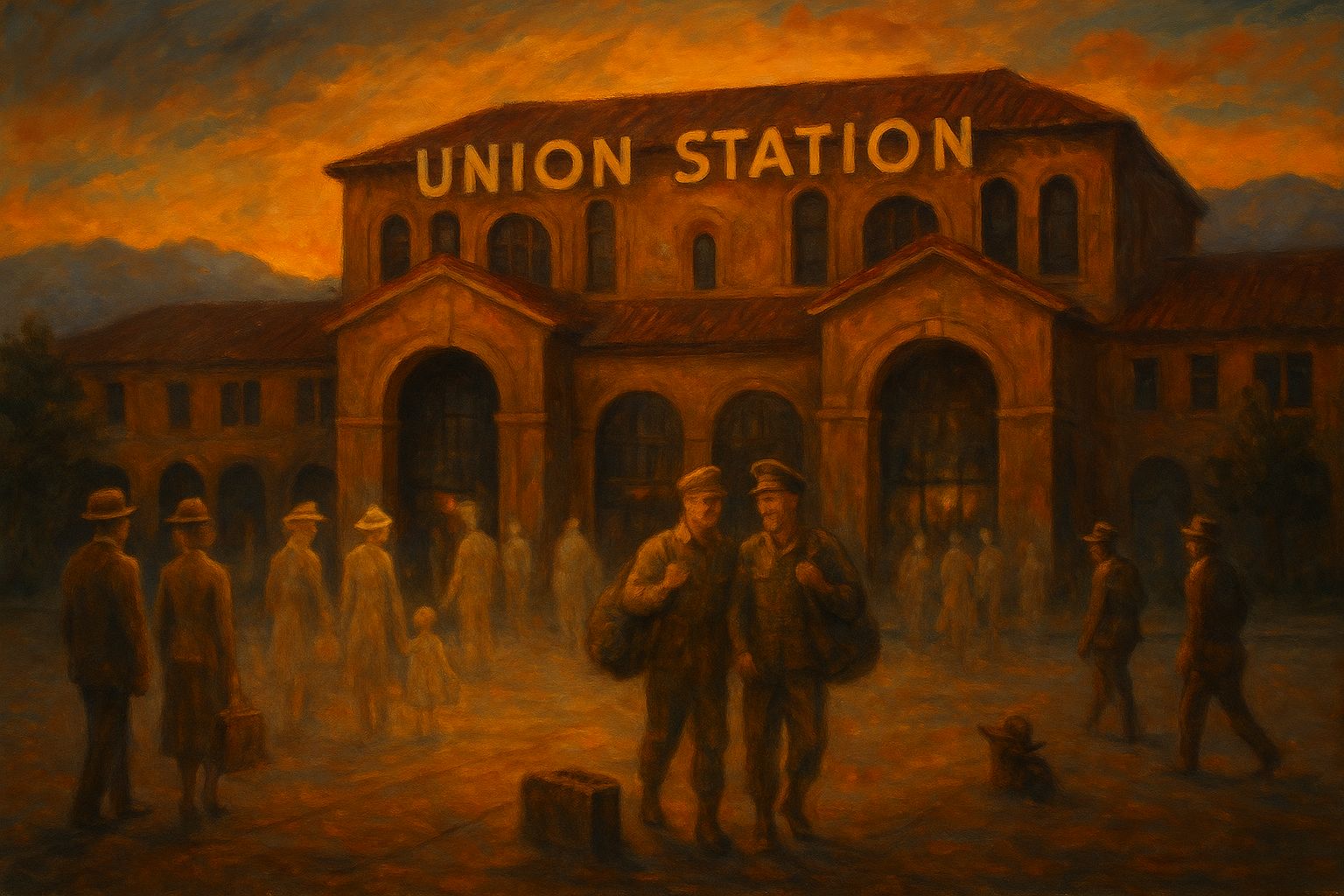

Ogden’s railroads roared back to life as the arteries of war. The same geographic position that made Ogden a 19th-century crossroads now meant that an endless stream of troop trains and freight trains converged here, moving men and matériel coast to coast. During World War II, “as many as 119 passenger trains passed through Ogden every twenty-four-hour period,” an astonishing tempo that harkened back to (and even surpassed) the city’s heyday as a railroad junction. Union Station bustled with servicemen coming and going at all hours. Tens of thousands of troops from across the country found themselves waylaid in Ogden – often en route to or from nearby Hill Field, or pausing on cross-country transfers – and they made the most of those layovers. The city offered these young GIs a last taste of fun and freedom before shipping out to uncertain fates. One local historian notes that Ogden became a rest stop where soldiers “got to spend that last moment here… alive and free and get to do whatever” they pleased before heading into battle. In practice, that meant a packed itinerary of drinking, gambling, and carousing on 25th Street.

Indeed, 25th Street during WWII was at its zenith of notoriety. Ogden had never tried very hard to hide its vice district – even local officials tended to look the other way – and during the war the city’s underbelly positively thrived. All the classic ingredients were present: bars and “soda parlors” (some still rigged from Prohibition days with hidden stills that could pour illicit whiskey straight from the tap), neon-lit pool halls and gambling rooms (many cleverly concealed behind innocuous storefronts), and of course brothels catering to every taste. So many “drinking establishments [had] popped up” by the 1910s that Prohibition barely slowed Ogden down – and now in the 1940s, demand was higher than ever. One could step off a troop train at Union Station and find all manner of sin within a few block radius. “You can’t go anywhere without coming to Ogden,” the old railroad slogan went – and for war-weary soldiers, that held true for pleasures as well as logistics.

Perhaps the most infamous establishment of the era was the Rose Room, a brothel on the second floor of 201 25th Street (a building that you might know by the name “Alleged”). In the late 1940s the Rose Room was ruled by madam Rose Davie and her husband Bill. By 1947, business was booming – the Rose Room pulled in an estimated $30,000 per month in revenue, an eye-popping sum for the time. Rose Davie herself became a local legend: she was known for her flamboyant style, reportedly decorating the brothel in plush pink and leopard print and keeping a pet ocelot on a leash. She even cruised around town in a shiny pink Cadillac, turning heads on Ogden’s streets. Inside her establishment, Rose installed a secret buzzer system to monitor the goings-on in each room and protect her girls. The Rose Room was just one of many houses of ill repute operating openly on 25th Street in those years – but its success and Rose’s colorful antics earned it outsized fame. And it wasn’t only vice for vice’s sake: Ogden’s booming wartime economy also fostered a vibrant cultural scene, especially in the city’s Black community. The same railroads that brought commerce had long brought Black railroad porters to Ogden, and during the war years their numbers grew. In 1944, local African-American leaders founded Ogden’s branch of the NAACP, led initially by Black women working on the home front (one early president, Ruby Price, came to Ogden to work at the Arsenal and stayed as a lifelong civil rights advocate). Segregation and discrimination were still harsh realities – many hotels and clubs downtown barred Black patrons – which is why the Porters and Waiters Club at 127 25th Street became such an essential institution. First opened as a rooming house for Black railroad workers in the 1910s, by WWII the Porters and Waiters could host over 100 men a night for 50 cents each, offering Black servicemen and rail workers one of the few places they could comfortably gather in town. They’d play pool and pinball, grab a beer and a sandwich, maybe gamble a bit. After the war, proprietor Anna Belle Weakley (who co-owned the club with her husband Billy) heeded the suggestion of a young saxophonist named Joe McQueen – and turned the basement into a jazz club. The result was legendary: a 250-capacity after-hours jazz venue where touring musicians would jam when they had a layover in Ogden or Salt Lake. “Great musicians like Fats Domino, B.B. King, and Marvin Gaye played at the club,” Anna Belle recalled, and by 1951 the Porters and Waiters had desegregated its audience, welcoming white fans in to mingle on the dance floor. In wartime Ogden, the nightlife truly swung.

By the time peace arrived in 1945, Ogden was a vastly different city than it had been in 1935. The population had ballooned and diversified, the economy was supercharged, and a frenzied energy permeated its streets. The federal government’s spending in Ogden during WWII measured in the hundreds of millions of dollars, and thousands of families who had come for war work now faced the question of whether to stay. Ogden’s official population jumped from about 43,600 in 1940 to 57,000 in 1950 – a 30% increase in one decade. (In reality, the metro area’s growth was even higher when accounting for the new suburbs spilling into neighboring Davis County.) The end of the war brought an initial moment of euphoria – victorious celebrations and the sudden absence of blackout drills and telegrams bearing bad news – but it also brought uncertainty. Many of the massive war contracts were canceled in 1945, and pink slips followed. Employment at the Ogden Arsenal, for instance, plummeted from 6,000 at peak to fewer than 1,500 workers after V-J Day. The Naval Depot in Clearfield likewise began scaling down, and rumors swirled that it might close (it did not). Nationwide, the postwar recession of 1946 hit many defense-dependent towns hard. Ogden, however, was somewhat insulated. The Cold War set in motion a new era of military spending, and almost as soon as one war ended, preparations for another began. In late 1950, with the outbreak of the Korean War, Hill Air Force Base and the Second Street depot both ramped up activity again. Ogden’s Army depot continued shipping supplies for U.N. forces in Korea, and Hill AFB was soon humming with aircraft refurbishments for the Korean conflict. This meant some continuity of jobs – and indeed by the mid-1950s the Defense Depot Ogden still employed roughly 3,000 civilians, far above pre-WWII levels. Even beyond overt military spending, the federal presence in Ogden remained strong: during the 1950s the big Army depot hosted new tenants like an Internal Revenue Service center, and other defense-related private firms (a Boeing aircraft parts plant, for example) set up shop in the area. In short, while Ogden’s wartime boom inevitably cooled, the city did not slip back into Depression-style bust. Instead, Ogden transitioned into the 1950s with a somewhat steadier, government-linked economy – and a society on the cusp of major cultural shifts.

Suburbia and Saloons: Ogden’s Postwar Balancing Act in the 1950s

As the 1940s gave way to the 1950s, Ogden found itself straddling two worlds. On one hand, it was a city flush with postwar optimism: a population boom was underway, the GI Bill was helping returning veterans buy homes and get educations, and new subdivisions were sprouting on what used to be farmland. On the other hand, Ogden still carried the baggage (and the allure) of its wilder days – particularly along 25th Street, which by the late ’40s had gained national infamy as a den of vice. The early 1950s would become a turning point, as civic leaders launched a concerted campaign to “clean up” Ogden’s image and steer the city into a new, family-friendly era.

One of the first signs of change was physical: suburban growth. The wartime housing crunch had been severe – with so many workers flooding in, Ogden and environs faced acute shortages. In response, temporary defense housing projects sprang up. One notable example was Washington Terrace, a large housing project built in 1942 to accommodate Hill Field and depot workers. After the war, rather than dismantle these homes, residents organized to turn Washington Terrace into a permanent community. In 1948 it incorporated as a city of its own, its very founding a direct product of the war. In fact, Washington Terrace’s charter President, George Herman Van Leeuwen, literally secured the land from the federal government to allow war workers to stay on as homeowners. By 1950, the new suburb had nearly 5,800 residents – most of them young families building a postwar life. Similar stories played out around the map. Just south of Ogden in Davis County, tiny farm towns like Sunset, Clearfield, and Layton that had hosted military installations now “became ‘bedroom communities’ to the depots,” filled with modest tract houses for thousands of defense workers and veterans. Ogden itself expanded outward: new residential tracts in South Ogden, the Lynn district, and other edges of the city drew those who wanted more space than the old urban blocks provided. This suburban migration was part of a broader cultural transition. The same folks who in their youth might have prowled 25th Street’s pool halls were now marrying, starting families, and seeking quieter lives with lawns and schools for their Baby Boom children. The car was king – and indeed, by the mid-50s, Ogden was eagerly anticipating the construction of the modern Interstate 15 highway through town, which would further enable suburban commuting (and hasten the decline of passenger rail).

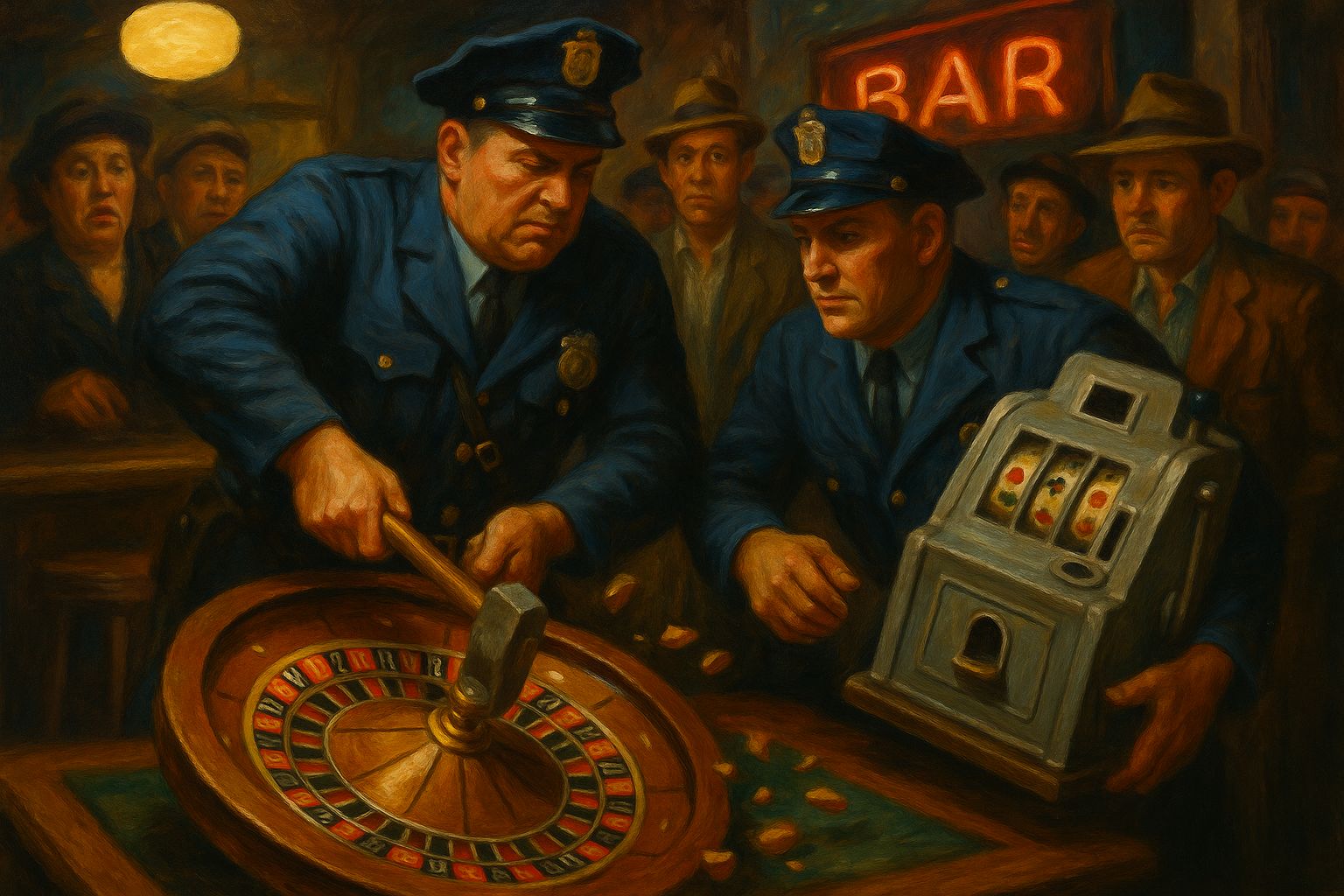

With this new suburban, family-oriented outlook came a clamor to tackle Ogden’s seedy underbelly. City leaders had tolerated or quietly managed 25th Street’s vices for decades, but by the late 1940s the pressure to reform was mounting. Competing forces were at work: local religious and business groups worried that Ogden’s reputation for sin would hinder respectable growth, while the military (ever a major presence) grew concerned that the city’s “wide-open” atmosphere was bad for troop discipline and health. (During the Korean War mobilization, Army officials fretted about rising venereal disease rates among soldiers passing through Ogden.) Thus in 1948 a new mayor, Rulon White, took office on a law-and-order platform and wasted no time in cracking down. Ogden police and the Weber County attorney formed a vice squad with “free reign to target businesses engaged in bootlegging, gambling, and prostitution.” Raids became frequent on 25th Street, often making a splash in the newspapers as slot machines were seized and smashed and bootleg liquor poured out on the gutter. Bar owners who had long flouted Utah’s quirky liquor laws (for example, by reselling liquor after hours at a markup) were shut down or forced to straighten up. Brothels that had operated with a nod and a wink from authorities suddenly found themselves padlocked. The crackdown even had a scientific sheen: the Utah Social Hygiene Association was brought in to survey prostitution and disease, and thanks to aggressive policing, “in 1952 Ogden reported a lower venereal disease rate than the state for the first time in several years,” a statistic city fathers pointed to with pride.

One by one, the stars of Ogden’s red-light district fell. In 1951, the glamorous madam Rose Davie – whose Rose Room had become almost synonymous with 25th Street vice – was finally put out of business, not by a morals charge but by federal tax evasion charges (the authorities, unable to pin more on her, nailed Rose and her husband for failing to report those lucrative earnings). The couple’s conviction landed them in prison for a time, and effectively marked the end of the Rose Room era. In 1954, police raided the beloved Porters and Waiters Club during a sweep; they caught Anna Belle Weakley serving liquor without a license and patrons gambling in back. One unlucky gambler drew a one-year jail sentence for his misdeeds. The club struggled on a few more years, but city authorities pressured the owners by revoking their beer license, and by 1959 the Porters and Waiters closed its doors. Similar fates befell smaller gambling halls and “bawdy houses” up and down 25th. By the mid-1950s, Ogden’s notorious Two-Bit Street was noticeably tamer than just a decade earlier. As one resident later recalled, by the end of the ’50s the street was no longer the glamorous den of sin it had been; it was shabby and half-empty, frequented mostly by a few die-hards and drifters. In a sense, the nail in the coffin came with changes far beyond Ogden: the railroad itself began abandoning Ogden. The 1950s saw passenger rail travel collapse across America due to competition from airlines and the new interstate highways. Ogden’s Union Station, which had seen 100+ trains a day in WWII, lost nearly all its passenger service by the late ’50s. The Southern Pacific and Union Pacific railroads re-routed or cut trains, and the bustling porters, redcaps, and vendors vanished. “Once the railroad stopped coming through, the entire town just sort of crashed,” as historian Sarah Langsdon put it – 25th Street was left to the drunks and the destitute, its grand hotels and saloons boarded up.

Luckily, this “crash” was not permanent. The very decline that gutted 25th Street in the 1960s meant that many of its historic buildings survived to be restored decades later, when Ogden reinvented itself yet again as a modern outdoor-oriented city. But that revival is another story. As the 1950s came to a close, Ogden was a city in transition. The wild war boom had subsided into the quieter rhythms of a regional center with a large federal workforce. The culture of the city had shifted: the emphasis moved from saloons and dance halls downtown to drive-in movies and suburban shopping centers on the outskirts. Yet, even in this more conservative phase, Ogden never entirely lost the gritty edge of its past. The memories of the war years – of thousands of uniformed men thronging 25th Street, of Rosie the Riveter working overtime at Hill Field, of jazz tunes spilling out of a basement club at 2 AM – remained part of Ogden’s identity.

Junction City Endures

Between the 1930s and 1950s, Ogden traveled a bumpy road from desperation to dynamism and into a new equilibrium. The lingering pain of the Great Depression gave way to the all-hands-on-deck mobilization of World War II, which in turn ushered in a postwar boom of babies, suburbs, and new challenges. Ogden’s evolution was driven by forces far beyond its city limits – global economic collapse, world war, Cold War – yet the city stamped its own character on these events. It remained, as ever, a “Junction City”: a crossroads where unlikely people and stories met. During these pivotal decades, Ogden was at once a buttoned-up Mormon town and a bawdy frontier outpost; a place where high-tech military depots and old-time saloons coexisted; where migrant farmhands, Southern Black jazzmen, itinerant soldiers, and fifth-generation locals all brushed shoulders on the street. The era left a tangible mark in landmarks like Ogden High’s art-deco façade and the sprawling warehouses on Second Street, and an intangible one in the memories and legends passed down. Looking back, it’s clear that the 1930s–50s fundamentally reshaped Ogden’s trajectory. By 1960, the city had grown more populous and economically diverse than ever before – yet it also bore the scars of boom and bust and the seeds of future change (for better and worse). Ogden had survived depression and war, cleaned up its “Two-Bit” Street (at least for a time), and emerged as a modernizing American city. In the vivid saga of Ogden’s past, those mid-century decades stand out as the crucible in which a rough railroad town was forged into a resilient community, tempered by adversity and enriched by a truly remarkable cast of characters and events.

NOTES FROM THE HORSE

“Neigh.”

Until next time,

Raw, weird, and local.